The Sermon Lacking That Old Thunder

By L. G. Merrick

Illustrated by Steve Morris

It was shortly before Christmas when my grandfather, the esteemed pastor Micah Hogue, delivered the one sermon I guarantee I will never forget. I doubt any of the world’s best people—as he called his congregation—ever would. What set it apart, right from the beginning, was not the snow that swirled outside the tall windows—that was ordinary enough; and not the way we sat crammed shoulder to shoulder in the old church—that was typical in any season. It was his voice. For all sixteen years of my life, his preaching had been music, smooth and clear, a croon for God. But that Sunday, the rasp he emitted could scarcely be heard. It was a dry, ragged sound that caused me to lean forward instinctively. As if a rusted hook had been stuck through my mind, and dragged me on—and, as it developed, into stranger parts than his speech usually ventured.

“I cogitate upon the desert,” he began.

He cast his gaze in the customary slow arc over us all. I noticed the new gap between his neck and shirt collar, how much weight he had lost just since last Sunday. His royal blue suit stood orderly as ever around him, but he no longer filled it.

“Sands. Barren sands,” he said. “No life. Not as we know life. Yes, the prickly cactus. The prickly scorpion. On and on the desert stretches, populated only by such prickles. An expanse, an emptiness, where you would walk for days and never meet any neighbor. Nor find a single shade tree. Where to survive, you must carry with you all you need, even simple water. Where the sun—which you love!—becomes your deadly foe.

“In the news once in a while, we spy a small item, don’t we? A tourist went for a hike in some desert. Arizona, often. Got out of sight, but only for three hours. Send in the search parties! Helicopters! It seems an overreaction. Yet there the poor man or woman lies, found stone dead. Dehydrated. Crumpled in the hot sand. Flesh baked until yellow-brown and crinkled like parchment—mummified, you see, by the harsh conditions. Already in appearance six thousand years lost.”

I certainly sat up straight at these details. I glanced to my mother for a hint at how to react. Is he going senile? She did not look at me. I detected a clench of concern in her jaw.

“It is hard for us to imagine the power of desert,” my grandfather, her father, continued. “A land so entirely opposite these bountiful hills of Kentucky that we call home.”

For days, he had been pale as a candle, but now I drew some reassurance from how gamely he mimicked his usual physical style. He gripped the sides of the podium, he rocked up on his toes to emphasize the key words. By the end of the sermon, I supposed, his thick white hair would be shaking dramatically, as always. The image comforted me.

“In our part of the world, the land offers such plenty, a resourceful man might carve out a long, happy life if he had nothing to his name but a pen knife. He would endure competition and lean times—but not cruelty. Whereas desert—desert would torture the same man, until he did not know his own name, and then it would kill him, in a span of hours. Without mercy. With full hostility. Avoid desert, all of you, steer clear!

“And wonder you might, as I have: Why did God choose to create such places? To what purpose? And subsequently, we might ask why, why was it into so terrible a landscape that He dispatched Moses, His favorite? Moses, and all the Chosen People! And then—when The Lord determined it was time for a New Covenant—why was it into desert that He sent to be born His own Son? Why? God dispatched His Hebrews into trackless wasteland, where they failed, and He learned nothing from it, and next He turned His only Son over to the same terrible land of lack and echo.”

The crowd shifted expectantly. I tried to imagine this delivered as it might have been weeks ago, in a peal of thunder instead of hissed. I looked across the aisle to my cousin Gwen for a sign she felt—well, sparked by his choice of topic, as I was.

Gwen and I had long shared a suspicion that the desert, or a desert, figured crucially in Grandpa Hogue’s younger days. There were two or three years he never spoke of directly. Likewise, he had never before sermonized extensively on desert. But we’d once overheard a late-night adult conversation that we did not completely understand, and it had become foundational to our secret impression of him. It contained some indication that as a young adventurer, rebellious and decadent, he had lived in the sinful state of California, in a palace, in a desert, and had fled from there back to Kentucky upon the occasion of some downfall or conflagration.

As to facts, we possessed but one: Periodically, the revered Micah Hogue disappeared from town. Not even his wife knew where he went, and we children were told it was not our business—which, naturally, left an impression. He had most recently disappeared four years ago, for a week. Had also disappeared when I was in second grade and Gwen in first. Had declared an intent to go away this recent autumn, coinciding with Halloween, but had been prevented from doing so at the last minute by unexpected church business—and this was a cause of consternation for him. Indeed, cancelation of that trip initiated the steep decline that was today so unavoidably evident in his dried-out voice and peculiar words.

But to me he remained practically one of the original apostles—the wisest and ablest servant of God I’d ever met. So these mysteries of his youth and disappearances only fed my personal theory: I believed that in the California desert fifty-ish years ago, he had experienced something holy, namely his own Saul-blinded-by-the-light moment; that he returned periodically to that spot where The Lord entered his heart, as a pilgrimage; and that he did so in order to be renewed in The Lord, for our sake.

Of course, it also all had something to do—surely it did—with the locked door upstairs in his house.

Gwen, who alone knew my Saul theory, mouthed across the aisle Let’s talk after.

“Jim. Face forward,” my mother said.

“Rome existed when Jesus was born!” he hissed from the podium. “Athens! Paris! Why was Jesus not born there? Surely any manger would do. Surely any sensible Father, rather than dead sand for His only Son, would have chosen—a fishing port of Spain! A peat-burning village of Scotland! The rich, black farmland of Germany! Or our Kentucky home. In that same year, God could have chosen a Cherokee Mary. A Chickasaw Joseph. All is within God’s reach, is it not? Is it not? So He might have chosen this ground, where our own church stands today, and out of Mary’s gory womb might have slid our Messiah into a pile of hay right here.”

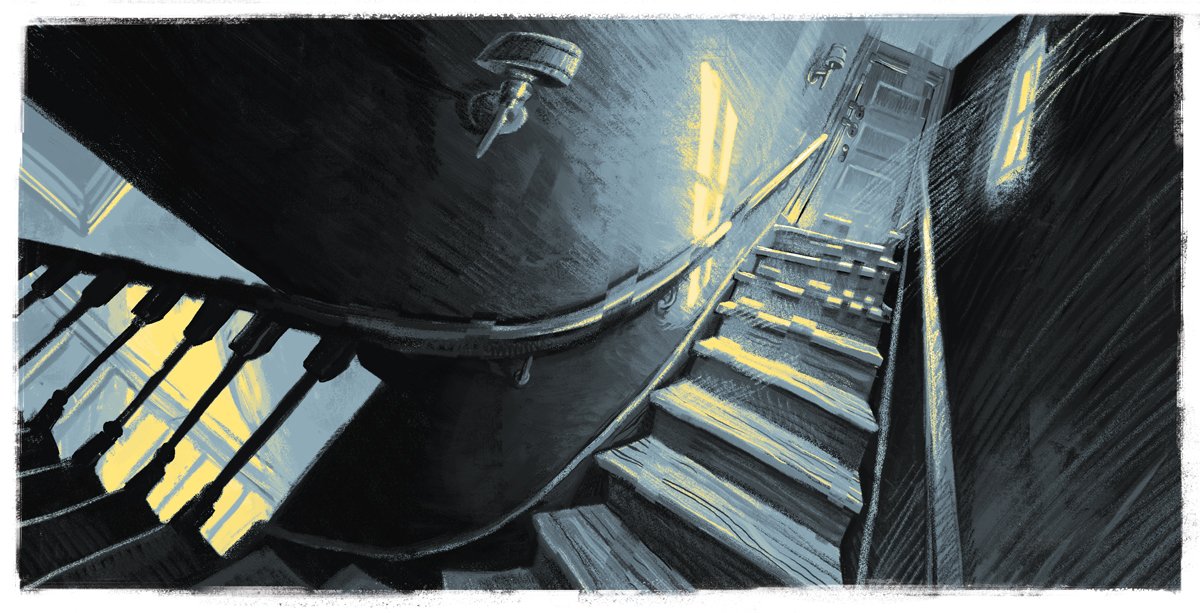

He pointed to the floor in front of the altar. Pointed a long while. Now no one could guess where he was going with this. We all sat as tense as frightened rabbits. Then he turned his head suddenly to the back of the church. The stare he drilled that way was enough to give the impression someone had burst through the doors, in rude style—I and several others half-turned to look. Of course we would have heard the doors, felt a blast of cold, if anyone had entered. When I turned forward again, on his face I perceived not only the unmistakable anger, as if at an interruption, but a second emotion, so subtle that I wondered if any except his close family could recognize it: a trembling fear.

Of what—I wondered.

Maybe he feared he had committed a defilement with his words. Gory womb. I myself felt nervous. On behalf of God.

I am called to be offended, I thought.

Well—there is no way Grandpa ends with questions and complaints. He will bring it home, I decided. He will make us see the hideous desert as he sees it on his pilgrimage. As beautiful, necessary, redeeming.

“This building, where we gather,” he said, “might have been a truly holy place. Might have. But instead… instead, God planted the all-important seed of our salvation in desert. Desert! Where nothing grows! Nothing—”

He broke into a jagged cough. A cough that rattled on and on, a hard scorched noise that rose and fell and even in its brief pauses, its gasps, kept him flailing. Past a point, some rose in the pews as if to assist him—including me—though none of us happened to be holding a glass of water, and none of us moved closer. And besides, he waved us back as he hacked and winced, even as he bent over clutching his sides.

At last it ended, and he straightened, and then paced. Paced before the altar, massaging his throat with one hand, tapping his breast with the other. Eventually he returned, red-eyed, to the podium.

“Dry are my lungs—because intense is the fire in my heart lit by The Lord.”

It was a joke he’d made after lesser coughs in previous sermons. This time no one laughed.

“So. Think on our Jesus. Born into a dead place. Wandering it, murdered in it. Now consider if Jesus had been born into a thriving kingdom. Envision Jesus plugged into bountiful land. Imagine Him the brightest lightbulb ever made, plugged into the world’s most powerful electric socket!”

He shook his fists, as if to threaten someone, and then flagged.

“No. God plugged Him into aridity. Remote from the millions He might save. Plugged Him into the absence of promise. What could our weaker and dimmer Jesus ever hope to accomplish?

“Do you realize, at the time of Our Lord’s birth, how many demons walked the world? Freely walked it? Thousands of thousands. Each the personification of wickedness. Each a unique torment to behold. Even now, I see one. I see one. The monster is faceless, and horned, and brazen. From a mouth open in its chest—a maw in place of a heart!—a dozen tongues lick! And with each step it takes, black sludge pours from its anus.”

A woman gave a curt scream of revulsion. There followed the sound of a husband trying to reassure her. I could not take my eyes off of Grandpa Hogue, who seemed to be a man no longer in decline but in freefall, off a precipice.

“And yes—yes—demonkind did shrink from the light of Jesus,” he raved, “but they shrank bit by bit. A quarter mile at a time, from that low-wattage light. If He had been born into vitality—banished, then, you demons! All of you, cast out of the world in a blink! Disintegrated by His searing radiance! And your desert sand turned miraculously to loam. To flowering meadow.

“If. If. Instead, you roam still. You rule your desert, and you roam even here. Into our town, into our own homes—come the demons. So cool and incomplete and failing is the light cast by The Lord. WHY?”

I thought of the locked door. That upstairs door was the strangest fact about my grandfather—or had been, until this sermon. The congregation did not know the door existed, and the family did not discuss it. But I had spent many hours of my childhood in his home, and so I knew: He permitted no one but himself to open it, not even our grandmother. And to guarantee we stayed out, on the door hung two padlocks in steel hasps, and a walk around the outside of the house showed all windows in that part converted to solid wall. No one except him had sneaked even a playful glimpse inside those rooms for forty years.

Of course I had incorporated all this into my conviction that he was a most favored servant of God. Behind the door—I imagined—existed a whole other, secret church, just for him. There, unwitnessed by unfit eyes, the full glory of his personal relationship with The Lord might blaze. There perhaps—out of a fire that burned without consuming anything—God’s holy voice advised him.

As to what actually was in there, I had one hint, and it made no sense. It was a suitcase. When he’d left on his trip four years ago, I’d carried the suitcase to the car for him. And it had weighed nothing.

“What did you pack in here, air?” I’d said, thinking myself an immortal wit.

Then when he returned, I watched him lug that same suitcase to the front door as if it weighed a ton. Trying to amuse me, I thought. So when he set it down just inside, in order to mop sweat from his brow, immediately I grabbed its handle. Expecting to complete his joke by hoisting it over my head and yelling in gorilla triumph.

The bag did not even rock. It sat as heavily as if filled with concrete.

Then sharply he ripped me from it. Gripped my wrists to hold my hands as far from my body as possible—as if they were coated in poison, were on fire. There was an element of panic about him. He spun me toward the sink, where he scrubbed my palms and fingers with plenty of soap—and, with the harsh pad, down to raw skin that bled in dots.

“I’m sorry! I’m sorry I touched your suitcase!” I cried.

“Sorry means nothing,” he said. “Go pray. Go beg God to protect you from your trespass.”

So mortified was I, I did not dare to wonder that day what was in the suitcase. All I knew was that he heaved it upstairs one step at a time, grunting, and locked himself into his secret room with it, while I prayed in the kitchen as commanded.

And now in this sermon, he proceeded to similar words.

“Maybe God did not have a choice. Where to birth Jesus. Maybe God depends on us. On Mary, a weary teen. On me, a frail old fool. On you, with your many trespasses. So tend His light with care, the way a man crossing desert takes care with the meager water in his canteen. That is your only chance—because demons are everywhere. Like roaches. Like dust. In every place, they abide. So carry God with tender care everywhere you go, as if into desert—a beautiful forest, the supermarket, your own home—everywhere, as if there you venture into a kingdom of evil!”

He looked triumphant as he said this, as if he had done it after all—seized victory for God—though myself, I didn’t see the victory just yet. I was even wondering how many of his past speeches I had misjudged to be victories.

He left the podium, as so often he did for the crescendo. He trod down the center aisle, voice at least crackling like kindling.

“And as you go, never forget the truth…”

In the past, whenever he approached the center of us, he did so turning from side to side, to meet every pair of eyes, as if to invite us all into a huddle. This time, he plodded straight on. As if his stare had locked onto the stare of that rude interloper who earlier might have kicked open the big doors. And more strangely, he slowed, and stepped lighter, as if increasingly he sensed that his next footfall risked shattering an ankle or hip. His triumphalism had fled him.

Halfway down the aisle, he stopped.

Sand, I thought abruptly.

In that suitcase—was it sand? Brought back from his personal Holy Land, for use in his private church?

I pictured him kneeling on a patch of desert, behind the locked door.

“Always carry this awful secret,” he said. “God the so-called Almighty is fragile. You will cross territories on your journey that He is doomed to lose. You stupid, foolish sheep! Beg Him to protect your soul! Not your body, but your soul—that He might extend Himself to do. Surely your body is lost! For our feeble God cannot guard your mortal vessel in a province of demon lords. They own the meat, and will devour it. But your soul. That He might be able to save—even in desert where His light never has fallen. You can expect to perish there—”

His voice seized in a knot. No doubt another powerful cough itched his throat, preparing to overtake him. In alarm, his veined eyes opened so wide they stood exposed as orbs. The congregation shifted in anticipation of the painful racket. But his lips stayed grimly set, and those absurd eyes only kept staring, on and on—until I forgot my worry about his health and sanity, and instead felt embarrassment at how terrified he looked of a simple cough that would not quite erupt; how comical he had become.

It was a long time he stood that way before anyone realized he was dead.

The end